Surgery, even if delayed, can restore vision in patients with brain injuries

Results promising even when operation delayed several months

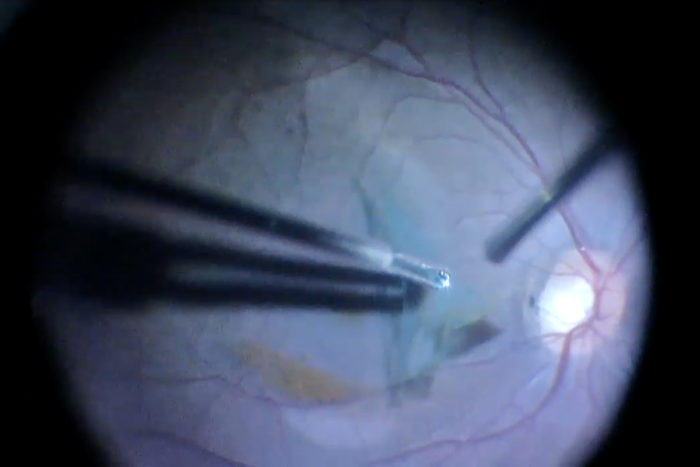

Courtesy of the journal Ophthalmology

Courtesy of the journal OphthalmologyDuring a retinal surgery, Rajendra Apte, MD, PhD, removes blood from a hemorrhage that had interfered with the patient's vision. Apte and his colleagues have found that such surgery can restore good vision in patients who have suffered traumatic brain injuries, even if the surgery has to be delayed for several weeks or months.

Surgery can restore vision in patients who have suffered hemorrhaging in the eye after a traumatic brain injury, even if the operation doesn’t occur until several months after the injury, according to a small study from vision researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Reviewing cases at three medical centers in different parts of the world, researchers found that surgery to remove the vitreous gel — which fills the space between the lens and the retina — netted 20/20 vision for most patients, even those who were legally blind before the operations.

The researchers, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Kresge Eye Institute at Wayne State University in Detroit and the L.V. Prasad Eye Institute in India, studied patients who developed hemorrhaging in the eye related to brain injuries suffered in motor vehicle accidents. Prior to surgery, some patients could barely detect a hand waved in front of their faces. But a few months later, the majority had 20/20 vision.

The study is available online in the journal Ophthalmology.

“These patients often have other issues related to brain injury, and we can’t work on the eye until a patient has stabilized,” said principal investigator Rajendra S. Apte, MD, PhD, the Paul A. Cibis Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Washington University School of Medicine. “It was important to learn how long we could wait to operate without having a negative effect on vision. In the majority of cases, it appears vision can be restored, even if the surgery is done several months after a traumatic brain injury.”

Accident victims and patients who experience brain aneurysms can develop bleeding in the back of the eye considered secondary to increased pressure in the skull due to hemorrhaging elsewhere inside of the head, a condition called Terson syndrome. Such hemorrhaging in the eye is serious because it causes vision loss and indicates that a patient’s life may be in danger.

“When patients suffer from brain bleeds without any accompanying Terson syndrome in the eye, the risk for mortality is around 10 percent, but if there is hemorrhaging in the brain and the eye, mortality rates can be as high as 40-45 percent,” said Apte, who treats patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

The researchers analyzed results from 20 patients who had surgery for Terson syndrome, but because many develop hemorrhaging in both eyes, the scientists were able to examine the effects of surgery in a total of 28 eyes. The researchers divided patients into two groups: those who had the operation, called a vitrectomy, within three months of the hemorrhaging; and those who had surgery after the three-month mark.

“We are very cautious and conservative with these patients because many have other injuries that need to stabilize before we try to correct their vision and because sometimes a hemorrhage will dissipate on its own and won’t require surgery,” Apte said.

In a vitrectomy, the vitreous gel that sits between the eye’s lens and retina, is removed and replaced with saline solution. Surgery in these patients helps restore vision by removing old blood that can prevent light signals from reaching photoreceptor cells in the retina following a hemorrhage.

The average vision in patients after their accidents but prior to their surgeries was 20/1290. Within one month of surgery, the average was 20/40. A few months later, almost all patients had 20/20 vision. There was no significant difference between those who had surgery right away and those who waited more than three months. The average visual acuity for all patients at the end of the study was 20/30, but that was partly due to three people in the study developing detached retinas that complicated their recoveries.

“In most situations where trauma causes bleeding in the brain that then leads to secondary bleeding in the eye, it seems likely that many patients will recover good vision after surgery, even if a few months pass before the operation,” Apte said. “The only caveat would be that if the bleeding in the brain injures part of the visual cortex or other visual pathways, that may make it impossible for the brain to process signals from the retina. With that in mind, patients always should be counseled about that prior to surgery, whether that surgery is done shortly after the initial injury or several months later.”