Podcast: Clinical trials launch to evaluate antimalarial, antidepressant drugs to treat COVID-19

Repurposing of FDA-approved drugs is fastest way to launch COVID-19 clinical trials

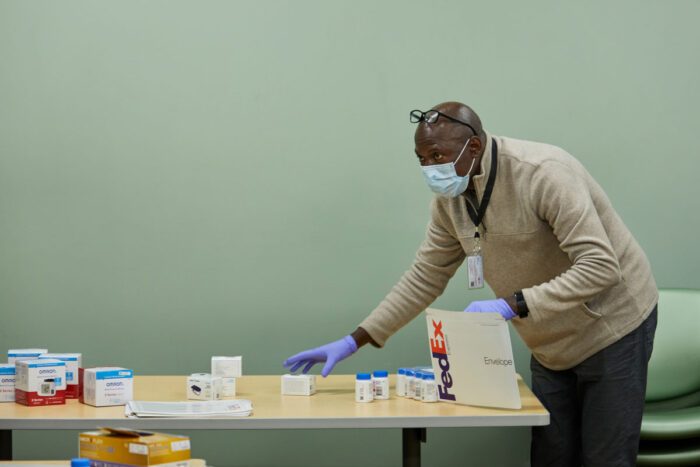

Clinical research assistant Leonard Imbula packs medication and medical equipment to be sent to participants in a COVID-19 trial that will help determine whether the psychiatric drug fluvoxamine might help prevent the life-threatening “cytokine storm” that lands many COVID-19 patients in the hospital. The Healthy Mind Lab at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis is conducting the clinical trial.

A new episode of our podcast “Show Me the Science” has been posted. At present, we are highlighting research and patient care on the Washington University Medical Campus as our scientists and clinicians confront COVID-19.

Although anecdotal reports have suggested certain therapies help some patients, there still are no proven treatments for the disorder. In this episode, we discuss repurposing existing drugs to treat COVID-19. One study involves treating hospitalized patients. Another involves providing infected patients with a drug to take at home as a way to prevent them from worsening and having to go to the hospital.

The trial in hospitalized patients is evaluating the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. Infectious diseases specialists Rachel M. Presti, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine, and Jane O’Halloran, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine, give COVID-19 patients one of the drugs — either in combination with the antibiotic azithromycin or by itself — to see whether such treatments might speed recovery and prevent some of the worst problems associated with the viral infection.

In another study, researchers are repurposing a psychiatric medication to try to prevent the excessive inflammatory response to the virus that lands many in the hospital. Eric J. Lenze, MD, the Wallace and Lucille Renard Professor of Psychiatry, and infectious diseases specialist Caline Mattar, MD, an assistant professor of medicine, are testing the drug fluvoxamine. Normally used to treat psychiatric problems, the drug also inhibits a receptor linked to inflammation. The researchers are delivering the drug to COVID-19 patients at their homes. They then check in with the patients via computer or smartphone to monitor vital signs for several days while the patients take fluvoxamine.

The podcast “Show Me the Science” is produced by the Office of Medical Public Affairs at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Related: Study to evaluate antidepressant as potential COVID-19 treatment

Related: Study to evaluate antidepressant as potential COVID-19 treatment

Drug fluvoxamine may help prevent life-threatening ‘cytokine storm’

Transcript

[music plays]

Jim Dryden (host): Hello, and welcome to Show Me the Science, a podcast about the research, teaching, and patient care, as well as the students, staff, and faculty at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, the show-me state. My name is Jim Dryden, and I’m your host this week.

At present, we’re focusing these podcasts on COVID-19. Doctors and scientists all over the world have been scrambling to understand how COVID-19 affects us. And this week, we’re speaking with researchers who are repurposing existing drugs to see whether they might help some patients. In one of the new studies, doctors will investigate the effectiveness of different combinations of the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine with the antibiotic azithromycin. After we hear about those studies, we’ll talk to a second set of researchers about a study using a different drug to try to keep COVID-positive outpatients from having to be hospitalized. But first, we’re joined by Rachel Presti, an associate professor of medicine, and by Jane O’Halloran, an assistant professor of medicine, both in the Division of Infectious Diseases. O’Halloran says it’s important to determine whether these antimalaria drugs really work.

Jane O’Halloran, MD, PhD: We have heard a lot of these drugs mentioned over the last couple of weeks. And I think for us, we wanted to make sure that we put a structure in place around, potentially, the delivery of these treatments. We felt the best way to put that structure in place was through a clinical trial to see could we learn more about the safety and efficacy of these drugs and combinations of these drugs?

Rachel Presti, MD, PhD: To sort of take a step back, there was some data published–

Dryden: Infectious diseases specialist, Rachel Presti.

Presti: –between a whole variety of potential drugs that might treat this new virus. Of the ones that were actually looked at, chloroquine and its related drug, hydroxychloroquine, both came up as having pretty decent potency against the virus in the lab. The idea behind the study was there are a couple of different regimens that people were trying, but it was all just single arm, a couple of patients. We think they did better than the people that we compared them to that somebody else was treating.

Dryden: What do you think about using these sorts of unproven therapies outside of clinical trials, before clinical trials? I realize that there’s not a whole lot of options for doctors trying to treat these patients, but what’s the downside to using these without actually conducting the sort of rigorous clinical trial?

O’Halloran: The thing about it is we know how they perform in certain disease states. We don’t know how they perform in this disease process. And without examining that, we can’t be 100% clear that they will act in the same way as they would when we use them in other disease states.

Dryden: What typically are the potential side effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine? What would be the contraindications in a patient who’s not a COVID patient?

Presti: They can affect the way the heart electrical conduction goes. And so people can get arrhythmias from them, particularly if they’re on other medications that also can have the same effect. That’s the side effect that we worry about the most. There’s also a side effect of retinopathy or visual problems. That’s usually with much longer courses. So those are some of the major, major ones that we try to avoid.

Dryden: This study is not only trying to determine whether these drugs work but which ones work and in what combinations. So you’re looking at chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine alone and in combination with azithromycin. Are those the four arms of the study? Did I get that right?

O’Halloran: That is correct, yes, the idea of if the addition of azithromycin to either of the other two drugs potentiates the effect and makes it a more successful treatment.

Dryden: Why might that? I mean, azithromycin is an antibiotic. This is a virus. When you get a cold, you’re not supposed to be taking antibiotics. What’s going on here?

Presti: They tried a whole variety of different drugs that were available. Some of them were drugs that had previously been used for SARS or MERS or other viruses. They grow up some cells. They infect the cells with virus. And they screen through a whole bunch of drugs to find ones that actually look like they stop the virus from growing in the cells.

O’Halloran: That’s usually the first stage in this process. And then you move through different stages if you were developing a new drug. I suppose the reason you move through the different stages is because you need to have a determination as to whether these drugs work first in the cells. And then if they work, is it something that’s safe to use in humans? So that’s the different phases of the clinical trials. By using drugs that we’ve already used in humans and that we know in other disease processes have been safe to use, you can potentially repurpose some drugs with some evidence that they have some in-lab activity.

Dryden: Who gets the drugs in this study? Are you looking to give these to newly admitted patients? I mean, I know they’re at the hospital when they would receive the drug, but is there a particular profile where you think the drugs might be more successful?

O’Halloran: Hospitalized patients who are not requiring mechanical ventilation. So we would assume that these patients would be at least mild to moderate in severity. Patients with very mild disease don’t require admission to hospital. And so it’s usually those kind of in the more moderate category, with the hope that this could potentially decrease or slow down the worsening of the disease course.

Dryden: How long would the patients receive some sort of treatment like this?

O’Halloran: All study arms in the study, the participants receive five days’ worth of treatment. So irrespective of the duration of their symptoms, it’s a five-day treatment course. It’s not very long treatment courses. We would hope that we wouldn’t be in a position where we would be seeing any long-term toxicities from these.

Dryden: And when will the first patients at Barnes-Jewish be enrolled and start receiving this sort of treatment? Is it this week sometime?

O’Halloran: It’s underway. It was quite a short timeframe from study conception to getting it off the ground. And I think COVID-19 is really showing us the teamwork. And there has been a huge effort by a number of researchers, and the research team here at Washington University, to make this study happen. From that perspective, we’re really amazed at the ability to do things when we’re under pressure.

Presti: I would just second what Jane said. This was a tremendous team effort. Probably the fastest study I think I’ve ever heard. From conception to first enrollment, I think, in 13 days.

Dryden: My understanding is that one thing that was lucky for this study is that Express Scripts, a subsidiary of Cigna, donated large quantities of the medications that you’re using in this trial. That since it’s been talked about in the lay press, it has sort of disappeared.

O’Halloran: There have been shortages of many of these drugs and many other drugs that we commonly use due to supply chain issues, because of manufacturing issues arising from COVID-19. So securing drug supply for this or any other study is a huge concern.

Dryden: While Jane O’Halloran and Rachel Presti work with hospitalized patients, Eric Lenze and his colleagues are studying a drug to keep patients out of the hospital. The drug is primarily used in psychiatric patients. It affects serotonin levels in the brain. But it turns out that the drug, fluvoxamine, also might be able to reduce inflammation and prevent some of the most serious problems experienced by the sickest COVID-19 patients. Lenze and coinvestigator, Caline Mattar, are testing fluvoxamine in those who have tested positive and are quarantined at home. Here’s Washington University psychiatrist, Eric Lenze.

Eric J. Lenze, MD: People may have heard a lot in the media about what’s called drug repurposing. There are thousands of drugs out there that have already gone through rigorous testing and approval by the FDA. They’re known to be safe and effective for some reason. But many of these drugs actually have other effects that might be used to fight COVID. And the quickest pathway to getting a drug out there is a drug that’s already been approved by the FDA for another reason.

Dryden: Could you tell me about your thought process over the last few weeks, how this idea came to you guys and how this kind of came about?

Lenze: It’s certainly counterintuitive to people, but perhaps no less counterintuitive than using a malaria drug. We may use some of these drugs as compassionate care, but we really need hard data to know whether they work or not.

Dryden: Dr. Mattar, this is a drug that is known to target something called the sigma-1 receptor. Could you tell me what that means “in English?”

Caline Mattar, MD: So what we know actually about COVID disease is that there are two phases for the illness. The first one is actually caused by the virus itself infecting the body and the cells and causing people to feel ill. But then the second phase of the illness, we believe — and the information that we have so far seems to suggest — that there is a response from the body itself, an inflammatory response, whereby people get super sick just because of the body reacting to the virus. So part of that is what we call the cytokine storm. And this is a really big term, but what it really means is that the body is having a very strong inflammatory reaction. So what the medicine is supposed to do is actually prevent that second part of the illness, the body’s really bad and strong response to the virus that is getting people very sick, getting people into the hospital, on ventilators, etc.

Dryden: Right. So this study is targeting patients who are sick but are not sick enough to be in the hospital.

Mattar: Exactly. So what our hope is is that we target the patients who are initially well enough to be at home and prevent them from getting sick and getting to the hospital by using the drug fluvoxamine.

Dryden: This is one of your specialties, Dr. Lenze, is virtual studies where you’ve got people that aren’t necessarily coming to the office, you’re not necessarily going to them. You’re communicating the way we’re communicating right now, over the computer.

Lenze: Yes. The unique thing about this study is it’s designed for outpatients. If you think about someone who’s symptomatic and COVID-positive, it’s going to be hard for them to go into get medical care. They are and should be quarantined at their home. All aspects of the study are done remotely with participants through their phones, computers, and email.

Dryden: This is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, correct?

Lenze: Yes. Correct. So it’s a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, which is the active mechanism of most of the commonly used antidepressants, like Prozac or Paxil. So fluvoxamine was approved decades ago. Its actual FDA indication is for obsessive-compulsive disorder. But it also has a separate effect, as Dr. Mattar said, on the sigma-1 receptor, which we think might block this cytokine storm and allow people to remain out of the hospital.

Dryden: The reason I asked you that, though, is that at least in the brain, a lot of antidepressants take a while. I’m assuming that you believe that its effects on this sigma-1 receptor would be much more rapid.

Lenze: Its effects in the body hitting the sigma-1 receptor are instantaneous. So we think it should– as soon as someone starts taking the medication, its effects should start to kick in immediately. Now let me just say that there’s a lot we don’t know about this. We don’t know whether this drug will actually have a beneficial effect in COVID patients. Its demonstrated to have this beneficial effect in what we call preclinical models, studies of animals where it’s been shown to prevent septic shock.

Dryden: What sorts of things would a patient do in this study? They would contact you and enroll, and then you ship them the drug. But will you ship them anything else?

Mattar: So things like measuring the oxygen level in the blood. And it’s going to be a very simple device that can be hooked up on somebody’s finger. A blood pressure machine that is automated, that people don’t really need to do much, except press a button for them to get that reading. As well as a thermometer so that we can measure their temperature and identify if they’re having a fever. So those would be some of the simple things. And the other aspect of it will be via conversations with the participants to also ask them about their symptoms.

Dryden: And it also, I guess, has the advantage of even if this drug doesn’t work, somebody is going to be monitoring this person so that if he or she gets into trouble, you could be saying, “Hey, something seems to be going on here.”

Mattar: Yeah, absolutely. So part of what we’re doing, as Eric mentioned, monitoring people’s vital signs, etc., is that we are going to be able to recognize when oxygen levels drop, etc., which are some of the earliest signs of clinical deterioration that we have identified in COVID patients.

Dryden: I would imagine that with this particular study you’ll know whether this is working pretty quickly.

Lenze: I would say in general, this is a much more rapid study from start to finish for a given patient or for the entire study than what we’re used to. We’re not just repurposing a drug here, but we’re repurposing ourselves. We’re taking an entire clinical lab that heretofore has been focused on testing treatments for mental health and repurposing the whole lab towards fighting this virus.

Lenze: It seems like the goal of this would be to keep people out of the hospital.

Mattar: If we can get them to stay with mild symptoms but prevent them from getting really sick, coming to the hospital, and potentially progressing to needing to be on a ventilator, if we can stop that cycle, first of all we would be helping patients staying healthy, staying at home. We would be decreasing the burden on hospitals. We can get the healthcare system at a capacity to be able to treat all the patients who absolutely need to be in the hospital, while keeping others healthy after the virus infection at home.

Dryden: Caline Mattar and Eric Lenze are recruiting patients with positive COVID-19 tests and investigating whether the psychiatric drug fluvoxamine might help them avoid some of the worst symptoms of the illness. We also heard from infectious diseases specialists Rachel Presti and Jane O’Halloran who have launched a study in hospitalized patients, testing the effectiveness of the antimalaria drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, along with the antibiotic azithromycin.

Show Me the Science is a production of the office of Medical Public Affairs at Washington University School of Medicine. The goal of this project is to keep you informed and maybe teach you some things that will give you hope. Thanks for tuning in. I’m Jim Dryden. Stay safe.