Incoming medical students receive crash course in health disparities

Orientation program focuses on caring for underprivileged patients

Robert Boston

Robert BostonWalking through impoverished neighborhoods in St. Louis provided first-year students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis with a firsthand look at health disparities. Bob Hansman, an associate professor of architecture at the university, offered a historical perspective on poverty and health.

With no dabbling, first-year students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis plunged into the realities of health-care disparities during a four-day orientation in August.

The 124 students analyzed life expectancy and health disparities, such as gun violence rates by St. Louis ZIP codes, discovering an inordinate pattern of death and debilitation among the area’s poorest residents in segregated nonwhite neighborhoods.

They visited north St. Louis streets marked by weedy abandoned lots, cracked sidewalks and crumbling brick buildings boarded with plywood. They saw firsthand various obstacles confronting residents who desire basic transportation and healthy food as well as daily essentials such as toilet paper and diapers.

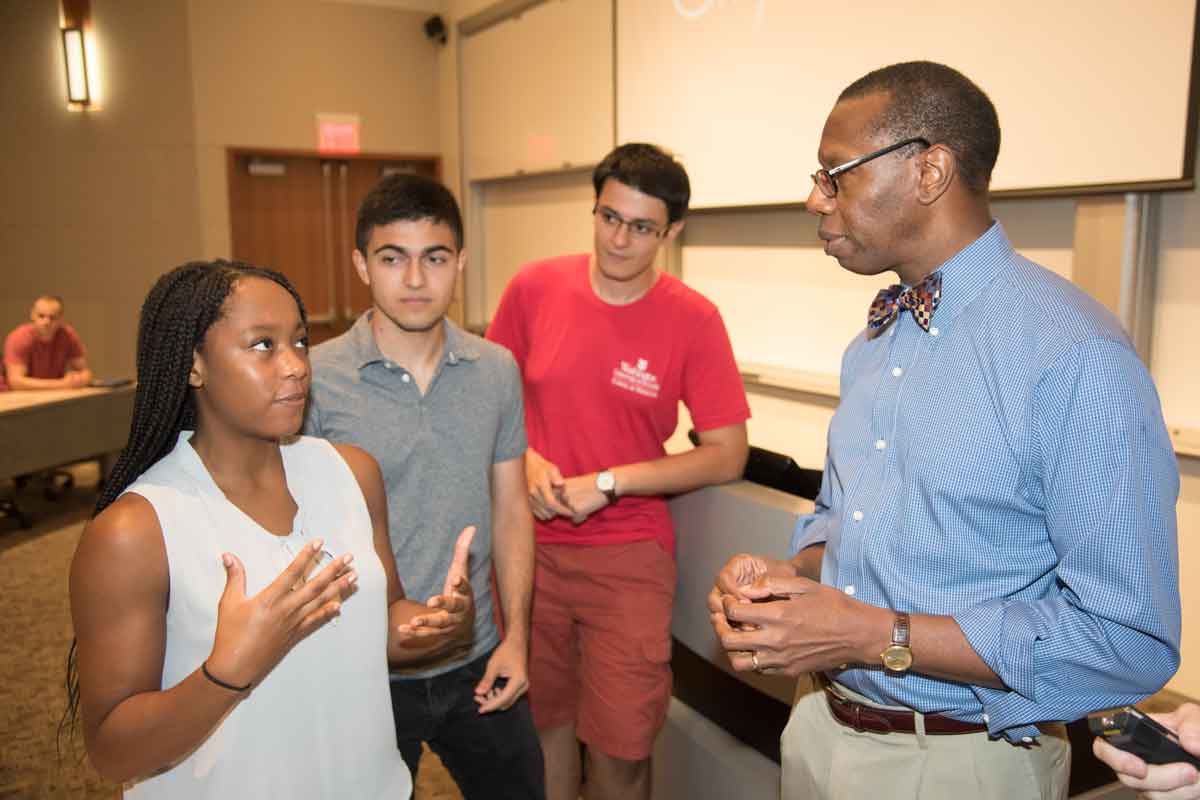

“There’s no sugar-coating,” said Will Ross, MD, the school’s associate dean of diversity and founder of the orientation program called Washington University Medical Plunge, or WUMP. “We take incoming medical students out of academic and clinical settings, out of the abstract, and immerse them into the realities facing underprivileged patients they may one day treat.”

In recent years, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has urged medical schools and teaching hospitals to look beyond singularly treating an ailment or disease. Instead, it advocates additional lessons about social and economic factors influencing individual health. The medical field refers to such circumstances as “social determinants of health.”

An AAMC report released earlier this year estimated that social and economic factors contribute to at least 40 percent of negative health outcomes. Causing it, in many cases, are health inequities, or “systematic, measurable and avoidable health differences between populations that stem from social factors such as racism, poverty, lack of healthful food, and homophobia (that) result in disproportionate disease and death for the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, persons living with disabilities, LGBT communities and others.”

WUMP’s emphasis and hands-on approach to teaching about health disparities started in 1999, before most medical schools considered the topic curriculum-worthy. The program became mandatory in 2014.

“It is an intense experience,” said Ross, who also is a professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology. “Students have said that after WUMP, they are not the same. They have more empathy and a broader outlook on the social factors that impact the health of a community and their patients. We want that kind of emotional impact because ultimately it translates into more compassionate, patient-centered care.”

Robert Boston

Robert BostonFor example, Ross recalled a recent patient who arrived at an appointment two hours late. “Most patients who are very late do not get a second chance to be seen on the same day, but I don’t like to turn away patients,” he said. “I want to see what may have caused the tardiness.”

In this particular case, the man could not afford transportation and spent the morning walking several miles to his appointment. “This man has no social support and spent a large chunk of his day trying to get to my office to get help for a medical problem,” Ross said. “I cannot improve his health if I turn him away. Our goal is to train future physicians to ask themselves, ‘What’s going on in my patient’s life that may affect his health?’”

Besides the poor, other groups addressed in WUMP sessions included immigrants and refugees, criminals and victims of crimes, the mentally ill, members of the lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender community, ethnic minorities, and women and children.

Presenter Lindsey Manshack, a research assistant at Washington University’s Buder Center for American Indian Studies, told students that despite the fact more than 160,000 American Indians live in Missouri and Illinois, no Indian Health Services (IHS) programs are located here. IHS is the federal health program for American Indians and Alaska natives. “This makes it impossible for many American Indians to experience quality health care,” a problem exacerbated by their inability to qualify for health insurance if they are impoverished, she said. Many American Indians fall into the “Medicaid gap,” unable to qualify for Medicaid and unable to afford health insurance on the exchanges.

“Our session provided a look at the current state of health disparities and common health conditions experienced by American Indians, as well as tips on working with this group in a culturally competent way,” said Manshack, a 2017 master’s of public health candidate at the Brown School. “Incoming medical students will be able to use this information throughout their careers in St. Louis and beyond.”

Medical students appreciated presentations from social work and public health students at the Brown School, Ross said. “One positive result of the program is that medical students recognize they need the collaboration of other disciplines to fully deliver the holistic care that patients deserve,” he said. “In the spirit of interprofessional education, the WUMP format hopefully will be adopted by programs in occupational therapy, physical therapy, nursing and even extend into graduate medical education.”

Robert Boston

Robert BostonIn a session on racial bias in medicine, led by Washington University alumna and biological anthropologist Sarah A. Lacy, PhD, students examined flawed scientific research implying that race is embedded in a person’s genes.

“Think back to your MCAT exams,” Lacy told the students. “If a patient is described in a test question as African-American, what’s the likelihood the answer is ‘sickle cell anemia?’

“Race is not biological but it affects your biology,” said Lacy, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Lacy argued that implicit bias exists among many physicians and that “black patients get less time with their physicians, receive more expensive hospital stays and experience a greater risk of death.”

Students said one of WUMP’s most impactful activities was a tour of a predominantly African-American neighborhood in north St. Louis near the School of Medicine campus. Led by Bob Hansman, an associate professor of architecture at Washington University, students in sandals and heels trudged dirt paths — past waist-high weeds, broken glass and discarded fast-food wrappers — to the old Pruitt-Igoe site, a failed urban housing project marred by poverty and violence. It was torn down in the mid-1970s, the lot abandoned ever since.

“The city has turned its backs on this neighborhood and the people who have lived here for generations,” Hansman said. “Before Ferguson, there was Pruitt-Igoe.”

Many students said time spent in north St. Louis helped visually connect the link between environment and poor health. For instance, obesity and related conditions such as high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are major problems among residents, partly because a healthy lifestyle is unaffordable and hard to sustain. A lack of grocery stores in the area makes access to fruits and vegetables difficult while a fear of crime makes outdoor exercise risky.

“I felt like I had a decent understanding of health-care disparities until WUMP,” said Caitlyn Brashears, a first-year student from Amarillo, Texas. “But I learned I was not as well-informed as I thought I was.

“Mr. Hansman’s talk and tour were very convincing and emotional experiences for me,” Brashears said. “Hearing stories depicting how these entrenched racial divides and disparities are actually experienced by individuals gave me a small understanding of the weight of human suffering that underlies all the data and charts. Mr. Hansman’s seemingly endless capacity for empathy was inspiring. I hope to emulate his courage, understanding and compassion in my future career.”

Robert Boston

Robert Boston