Immune-boosting compound makes immunotherapy effective against pancreatic cancer

Chemical compound extends survival by months, in mice

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn immune cell (blue) attacks a cancer cell (yellow) in this computer-generated image. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Rush University in Chicago have found a compound that promotes a vigorous immune assault on pancreatic cancer. The findings, in mice, suggest a way to improve immunotherapy for the deadly disease in patients.

Pancreatic cancer is especially challenging to treat – only eight percent of patients are still alive five years after diagnosis. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are of limited benefit, and even immunotherapy – which revolutionized treatment for other kinds of cancer by activating the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells – has been largely ineffective because pancreatic tumors have ways to dampen the immune assault.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Rush University in Chicago have found a chemical compound that promotes a vigorous immune assault against the deadly cancer. Alone, the compound reduces pancreatic tumor growth and metastases in mice. But when combined with immunotherapy, the compound significantly shrank tumors and dramatically improved survival in the animals.

The findings, published July 3 in Science Translational Medicine, suggest that the immune-boosting compound could potentially make resistant pancreatic cancers susceptible to immunotherapy and improve treatment options for people with the devastating disease.

“Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease, and we are in desperate need of new therapeutic approaches,” said co-senior author David DeNardo, PhD, an associate professor of medicine and of pathology and immunology at Washington University School of Medicine. “In animal studies, this small molecule led to very marked improvements and was even curative in some cases. We are hopeful that this approach could help pancreatic cancer patients.”

On paper, immunotherapies for pancreatic cancer seem like a good idea. The technique works by releasing a brake on specialized immune cells called T cells so they can attack the cancer. In the past, researchers working in the lab found they could release the brake and prod T cells into killing pancreatic cancer cells. But when doctors tried to treat people with pancreatic cancer using immunotherapies, fewer than five percent of patients improved.

This failure of immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer has puzzled scientists. But T cells aren’t the only player in the immune assault on cancer. Myeloid cells, another kind of immune cell found in and around tumors, can either tamp down or ramp up the immune response. They tilt the playing field by releasing immune molecules that affect how many T cells are recruited to the tumor, and whether the T cells show up at the tumors activated and ready to kill, or suppressed and inclined to ignore the tumor cells. In pancreatic tumors, myeloid cells typically suppress other immune cells, undermining the effects of immunotherapy.

DeNardo, co-senior author Vineet Gupta, PhD, of Rush University, and colleagues realized that releasing the brake on T cells might not be enough to treat pancreatic cancer. Unleashing the power of immunotherapy might require also shifting the balance of myeloid cells toward those that activate T cells to attack.

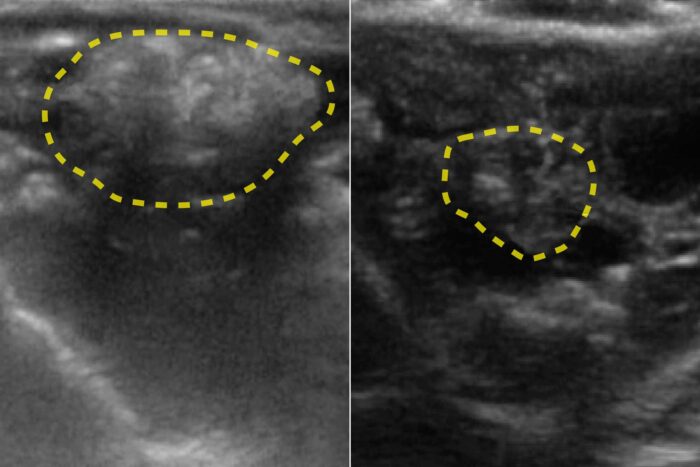

The researchers identified a compound, called ADH-503, that interferes with the migration of myeloid cells. Normally, pancreatic tumors are teeming with myeloid cells that suppress the immune response. When the researchers gave the compound to mice with pancreatic cancer, the number of myeloid cells in and near the tumors dropped, and the remaining myeloid cells were of the kind that promoted, rather than suppressed, immune responses. This environment translated into greater numbers of cancer-killing T cells in the tumor, significantly slower tumor growth and longer survival.

Then, the researchers – including first author Roheena Panni, MD, resident in general surgery at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and co-author William Hawkins, MD, the Neidorff Family and Robert C. Packman Professor of Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine – investigated whether creating this same environment could make pancreatic tumors susceptible to standard immunotherapy. First, they treated mice with a so-called PD-1 inhibitor, a standard immunotherapy used to treat other kinds of cancer. Unsurprisingly, they saw no effect. But when the researchers gave the mice the immunotherapy in conjunction with ADH-503, the tumors shrank and the mice survived significantly longer. In some experiments, all the tumors disappeared within a month of treatment, and all the mice survived for four months, when the researchers stopped monitoring them. In comparison, all the untreated mice died within six weeks.

Gupta noted that while pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, only about three percent of clinical trials for cancer immunotherapies target pancreatic cancer.

“Unlocking the promise of immunotherapies for pancreatic cancer requires a new approach,” Gupta said. “We believe these data demonstrate that targeting myeloid cells can help overcome resistance to immunotherapies.”

The strategy of boosting antitumor immune activity by shifting the balance of myeloid cells improved the effectiveness of other pancreatic cancer therapies as well, the researchers said. Mice treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy both fared significantly better when ADH-503 was added to the regimen.

“You can’t make a one-to-one translation between animal studies and people, but this is very encouraging,” DeNardo said. “More study is needed to understand if the compound is safe and effective in people, which is why Gossamer Bio, Inc., is starting phase I safety studies in people later this year at Washington University and other sites.”