How do tired animals stay awake?

Fruit flies yield clues to a good night’s sleep, insomnia

Joseph "Dave" Jones

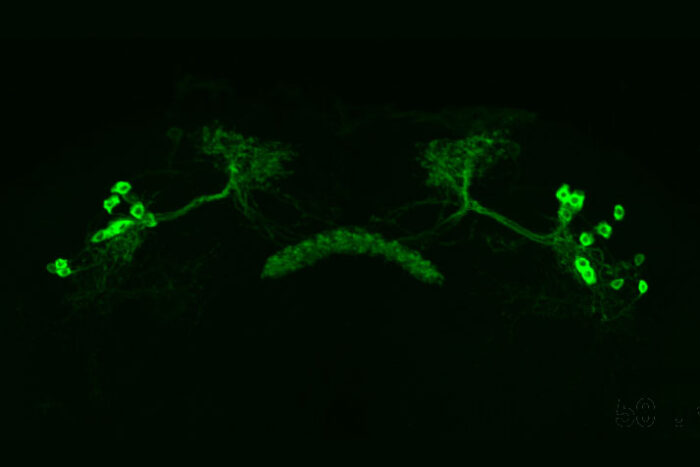

Joseph "Dave" JonesThe dorsal fan-shaped body pictured is a structure in the brains of fruit flies that controls their sleep behavior. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues have found that brain neurons in the dorsal fan-shaped body adapt to help the flies stay awake despite tiredness in dangerous situations and help them fall asleep after an intense day.

New research provides clues to falling fast asleep – or lying wide awake. Studying fruit flies, the researchers found that brain neurons adapt to help the flies stay awake despite tiredness in dangerous situations and help them fall asleep after an intense day. The findings, from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Missouri, Kansas City, are published online in PLoS Biology, and could lead to new approaches to treating insomnia and improving sleep quality in people.

“If you’re sick or sleep deprived, or you’ve just learned something new, you sleep more,” said co-corresponding author Paul Shaw, PhD, a professor of neuroscience at Washington University. “But if something dangerous is happening, your brain says, ‘No, no, no, no. It’s not time to go to sleep. I don’t care how tired you are.’ The neurons that regulate sleep can tell the difference between sleep when it’s safe and sleep when it’s dangerous.”

The sleep habits of fruit flies are a lot like ours. The flies are active in the day, sleep at night, and like to take a little nap in the afternoon, particularly on hot days. Caffeine keeps them up, and drugs that put us to sleep work on flies, too.

There is one crucial difference, though: Their brains are a million times smaller than ours, making it possible to identify the role each neuron plays in controlling fly behavior. Shaw and co-corresponding author Stephane Dissel, PhD — an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri who began working on this project while a postdoctoral researcher at Washington University — focused on 24 brain neurons that control whether a fly sleeps or wakes.

These neurons receive and respond to sleep signals sent by other neurons via chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters. The researchers investigated whether experiences that affect sleep behavior change how those 24 neurons respond to the neurotransmitters dopamine, which promotes wakefulness; glutamate, which promotes sleep; and allatostatin A, which also promotes wakefulness. Allatostatin A was previously known to play a role in feeding behaviors; as part of this study, the researchers showed that it also plays a role in regulating sleep.

Sleep reinforces memory and learning and fosters creativity. Both people and flies sleep more after an intellectually challenging day. As part of this study, the researchers showed that living in a crowded social environment or learning a new behavior trigger molecular changes in the flies’ sleep neurons that make them less sensitive to dopamine and therefore sleepier.

On the other hand, when the researchers alarmed the flies by periodically shaking the vials they live in during their sleeping hours, the flies’ brains produced both allatostatin A and glutamate. The combination of two opposing sleep signals kept the flies awake despite tiredness to cope with what they saw as a dangerous situation. The sleep neurons of naturally insomniac flies — insects that hatch with a tendency to sleep only half as long as typical flies — responded abnormally to sleep neurotransmitters, suggesting an inborn defect in how their brains regulate sleep.

“A lot of people don’t sleep well, and we really don’t know why,” Shaw said. “Our data suggests that there is a genetic predisposition to how neurological signals are interpreted by sleep centers in the brain. If the system goes astray, then you get these conflicting signals: You’re tired, but you can’t fall asleep. By understanding how these conflicting signals can arise, we can begin to think about how we might design therapeutics for people.”

Intriguingly, one intervention seemed to cause a lasting improvement to sleep quality: time-restricted feeding. Fruit flies normally eat all day, but for this study the researchers limited the flies’ access to food to between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. After a week, the flies’ sleep neurons were more sensitive to dopamine, and the sensitivity persisted for days after returning to a normal feeding schedule. The flies slept less, but they didn’t show signs of tiredness, an indication that the quality of their sleep had improved, the researchers said.

“Time-restricted eating is a hot topic right now,” Shaw said. “The claim is that confining your food intake to certain hours of the day will help you sleep better and maintain a healthy weight. The evidence that this works in people is mixed. But in flies, our data suggests sleep quality improves with time-restricted feeding. It’s possible that there’s an intersection between time-restricted feeding and sleep regulation that we can take advantage of to help people sleep better.”