Gene ID’d as potential therapeutic target for dementia in Parkinson’s

Targeting gene linked to Alzheimer’s may reduce dementia risk in Parkinson’s

Z.M. Wargel and B.M. Freeberg

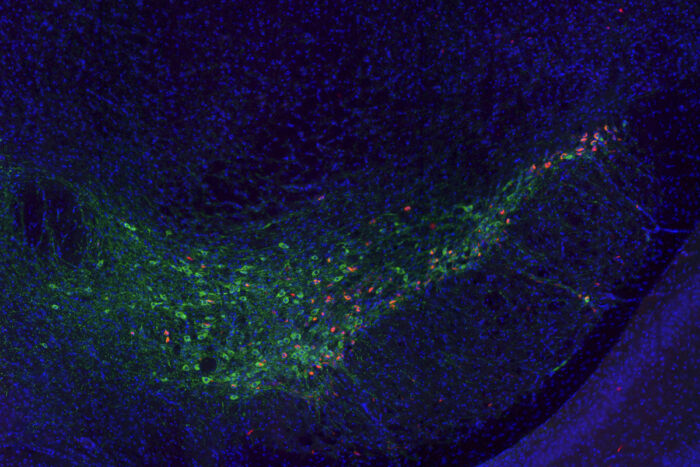

Z.M. Wargel and B.M. FreebergClumps of the Parkinson’s protein alpha-synuclein (red) are visible inside neurons (green) in the brain of a mouse. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered that the genetic variant APOE4 – long linked to dementia – spurs the spread of harmful clumps of Parkinson’s proteins through the brain. The findings suggest that therapies that target APOE might reduce the risk of dementia for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Dementia is one of the most debilitating consequences of Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological condition characterized by tremors, stiffness, slow movement and impaired balance. Eighty percent of people with Parkinson’s develop dementia within 20 years of the diagnosis, and patients who carry a particular variant of the gene APOE are at especially high risk.

In new research, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found a clue to the link between Parkinson’s, APOE and dementia. They discovered that harmful Parkinson’s proteins spread more rapidly through the brains of mice that have the high-risk variant of APOE, and that memory and thinking skills deteriorate faster in people with Parkinson’s who carry the variant. The findings, published Feb. 5 in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to therapies targeting APOE to slow or prevent cognitive decline in people with Parkinson’s.

“Dementia takes a huge toll on people with Parkinson’s and their caregivers,” said Albert (Gus) Davis, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology and the study’s lead author. “The development of dementia is often what determines whether someone with Parkinson’s is able to remain in their home or has to go into a nursing home.”

An estimated 930,000 people in the U.S. live with Parkinson’s. The disease is thought to be caused by toxic clumps of a protein called alpha-synuclein that build up in a part of the brain devoted to movement. The clumps damage and can kill brain cells.

Cognitive problems tend to arise many years after the motor symptoms. The protein clusters implicated in movement problems also are linked with dementia, but how this happens is not clear. Davis and his colleagues – including senior author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology – saw a clue in the risky nature of APOE.

A variant of APOE known as APOE4 raises the risk of Alzheimer’s disease threefold to fivefold. Like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s is a neurodegenerative condition caused by the spread of toxic protein clusters throughout the brain, although some of the proteins involved are different. APOE4 increases the chance of Alzheimer’s dementia partly because it spurs Alzheimer’s proteins to collect into clumps that injure the brain. The researchers suspected that APOE4 similarly triggers the growth of toxic clusters of Parkinson’s proteins.

Studying mice with a form of alpha-synuclein prone to clumping, Davis, Holtzman and colleagues genetically modified the mice to carry human variants of APOE – APOE2, APOE3 or APOE4 – or no APOE at all.

The researchers found that APOE4 mice had more alpha-synuclein clusters than APOE3 or APOE2 mice. Further experiments showed that the clumps spread more widely in APOE4 mice as well. Together, the findings showed that APOE4 was directly involved in exacerbating signs of disease in the mice’s brains.

“What really stood out is how much less affected the APOE2 mice were than the others,” Davis said. “It actually may have a protective effect, and we are investigating this now. If we do find that APOE2 is protective, we might be able to use that information to design therapies to reduce the risk of dementia.”

To study the effect of APOE variants on dementia in people with Parkinson’s, the researchers analyzed publicly available data from three separate sets of people with Parkinson’s. Two of the cohorts – one from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, with 251 patients, and the other from the Washington University Movement Disorders Center, with 170 patients – had been followed for several years. In both cohorts, cognitive skills declined faster in people with APOE4 than in those with APOE3. People with two copies of APOE2 are very rare, but none of the three patients in the group with two copies of APOE2 showed any cognitive decline over the period of the study.

The third cohort, from the NeuroGenetics Research Consortium, was made up of 1,030 people with Parkinson’s whose cognitive skills had been evaluated just once. The researchers found that people with APOE4 in the cohort had developed cognitive problems at a younger age and had more severe cognitive deficits at the time they were evaluated than people with APOE3 or APOE2.

“Parkinson’s is the most common, but there are other, rarer diseases that also are caused by alpha-synuclein aggregation and also have very limited treatment options,” Davis said. “Targeting APOE with therapeutics might be a way to change the course of such diseases.”

APOE doesn’t affect the overall risk of developing Parkinson’s or how quickly movement symptoms worsen, so an APOE-targeted therapy might stave off dementia without doing anything for the other symptoms. Even so, it could be beneficial, Davis said.

“Once people with Parkinson’s develop dementia, the financial and emotional costs to them and their families are just enormous,” Davis said. “If we can reduce their risk of dementia, we could dramatically improve their quality of life.”