Advances in brain tumor therapies offer speedier recoveries

Doctors and researchers are collaborating on the development of new advances in brain tumor therapies

Surgery remains a mainstay treatment for brain tumors, but advances in technology and new clinical trials mean patients have more treatment options—some noninvasive—and quicker recoveries.

“We have to attack brain cancer from all sides using different approaches,” says Albert Kim, MD, PhD, a Washington University neurosurgeon at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “That’s going to be the most effective strategy, and that’s what we offer here.”

Using next-generation brain tumor technology

Physicians at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University employ neuronavigation, which involves using computer-assisted technology that helps neurosurgeons navigate within the brain, as well as endoscopy, a scoping device to look inside a body cavity, for minimally invasive surgeries and other advanced tools. They’re also developing and using next-generation brain tumor technology, including:

- Improved brain mapping that allows neurosurgeons to monitor and protect critical brain areas while a patient is under anesthesia. Older technology allowed mapping only during awake brain surgeries.

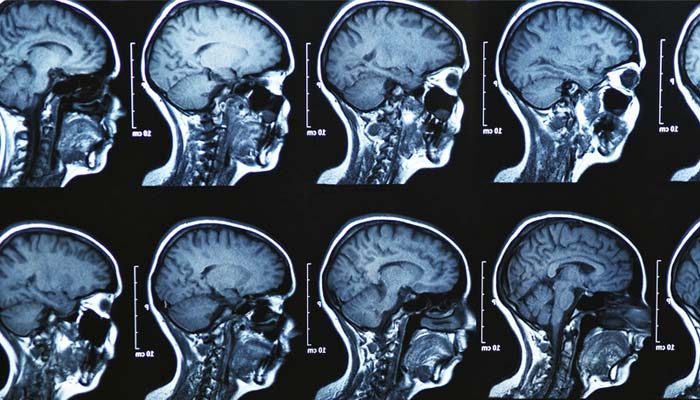

- Intraoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which allows surgeons to use imaging technology to identify diseased brain tissue before surgery is completed. In the past, a follow-up MRI was performed a day or so after surgery and, based on those results, some patients required a second surgery.

Washington University neurosurgeons also use an MRI-guided laser treatment that can reach deep-seated tumors traditionally thought to be inoperable and achieve successful outcomes. The procedure is especially helpful for patients with other medical disorders that make open surgery too risky. It also improves the effectiveness of chemotherapy on brain tumors, says David Tran, MD, PhD, a Washington University neuro-oncologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

“By heating up the tumor using this device, you can also disrupt the blood-brain barrier,” he says. This can increase the delivery of chemotherapy.

A clinical trial will further study the technology.

Ongoing clinical trials at Siteman

Other ongoing clinical trials at Siteman will study the effectiveness of brain tumor vaccines. One strategy calls for collecting fresh tumor tissue in the operating room and processing it in a lab into a “soup.” Next, researchers collect immune cells called dendritic cells from a patient and activate them using the tumor soup before they are reinfused into the patient in the form of a vaccine. A similar approach, currently available only at a few major cancer centers, is being used to develop personalized vaccines that use other immune cells called T cells, rather than dendritic cells.

Another type of vaccine targets a genetic mutation unique to glioblastoma, the most common high-grade brain cancer and the most aggressive. Early data from these vaccine drugs shows that patients who received the vaccine in addition to the current standard therapy live more than twice as long as patients who received standard therapy alone. The side effects were, in most cases, no worse than those of a flu vaccine, Tran says.

Genomic sequencing offers another step forward. By studying a patient’s DNA, researchers are learning which changes, or mutations, affect responses to a particular drug.

Such advances, whether in genomics, technology or basic science, could ultimately mean more treatment options and better outcomes, Kim says.

“There are parts of the tumor that cannot be treated with surgery, and we have to tackle them using other means,” he says.